Seamus Heaney Said It Better than We Ever Could

West Yorkshire Steel have always taken a level of pride in their knowledge of metallurgy and engineering steels, we know that steel has been part of not only its own revolution but has supported every section of modern life. For the modern age, the field of steel is a scientific, precise sector but the view hasn’t always been that way and nowhere is this more obvious than in the connotations of the word ‘blacksmith’.

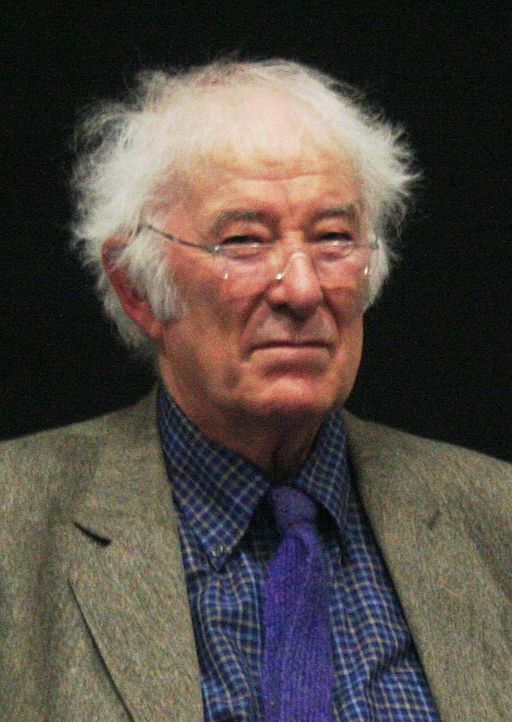

Village blacksmiths, the large, surly men with moustaches and dirty leather aprons are the epitome of the age and represent an entire industry in one word. Although these men were a huge part of the make-up of Old Britain, it’s rare that this image of heat, sweat and muscle wrangling out iron into horseshoes is seen as artistic or poetic; except in the case of Seamus Heaney.

Village blacksmiths, the large, surly men with moustaches and dirty leather aprons are the epitome of the age and represent an entire industry in one word. Although these men were a huge part of the make-up of Old Britain, it’s rare that this image of heat, sweat and muscle wrangling out iron into horseshoes is seen as artistic or poetic; except in the case of Seamus Heaney.

Heaney, as a young boy would walk past a forge on his way to school, hearing the ping of the hammer on the metalwork and managing to capture the whole experience in a short poem named simply The Forge.

All I know is a door into the dark.

Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting;

Inside, the hammered anvil’s short-pitched ring,

The unpredictable fantail of sparks

Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water.

The anvil must be somewhere in the centre,

Horned as a unicorn, at one end and square,

Set there immoveable: an altar

Where he expends himself in shape and music.

Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose,

He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter

Of hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows;

Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick

To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

In one short poem, Heaney manages to encapsulate not only his limited knowledge from only ever seeing ‘the door into the dark’ and the exterior of the workshop, but also show a total wonder of the process of forging metal into fully-fledged products.

His show of the blacksmith, the man with hairs in his nose who grunts and goes back to work is still one of the recognisable images of the kind of metalworkers who used to be so common across Britain, that the surname they sparked, ‘Smith’ is still the most common name in Britain today.

While literary theory and critique isn’t our particular specialist field, the short work by Heaney is a wonderful glimpse of not only the wonder and joy of seeing metal being worked, but also manages to capture in words a sight that would rarely be seen today, preserving in a way an entire way of life in not only a practical but romantically descriptive way.